How can communities protect their food systems from external influence?

Answering the above question is at the centre of a campaign being implemented by the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA) in more than 13 African countries including Zimbabwe. Dubbed My Food is Africa, the campaign started in 2022 with baseline surveys to understand local people’s perceptions about African food. In Zimbabwe, insights were gathered from more than 60 households of Harare, formal institutions like boarding schools, hospitals and universities, among other sources.

Collectively defining African food

Communities cannot protect what they do not know. To that end, the survey started by finding out the extent to which there is consensus on the definition of African food. Like other African countries, Zimbabwe has a diverse food basket comprising more than 100 commodities consumed in different communities at different times of the year. In addition to local supplies, some commodities are imported from neighbouring countries like Zambia, South Africa, Mozambique as well as from Asia. It is within this context that African food has to be defined in order to be protected.

Household consumers, traders and vendors could not give a holistic definition of what is meant by African or Zimbabwean food but they were comfortable in using alternative terms like ‘indigenous food’, ‘traditional food’ and Chikafu chechivanhu in shona vernacular language. The term indigenous food is used mainly to refer to the fact that the food has its origins starting from seed based on indigenous people’s knowledge and innovations. The food is considered traditional because consumers understand it to be closely linked to their culture and traditions. During interviews respondents were quick to give examples of small grains (sorghum; rapoko; brown rice and pearl millet); indigenous vegetables (muboora; munyemba; munyevhe; mutsine); tubers (madhumbe; tsenza; sweet potatoes and cassava) indigenous poultry and wild fruits; wild mushroom; edible insects; indigenous livestock (cattle; goats and pigs) as part of what they mean by purely African-Zimbabwe food basket.

Other respondents associated African-Zimbabwean food as that which is produced without use or heavy use of industrial seeds and chemicals. Their understanding is that characteristics of indigenous food production are closely related to nature and climatic conditions. Most of the respondents indicated they have had this exposure and knowledge from their home areas where they grew up producing these commodities. Urban consumers confirmed these commodities are produced with very little or no industrial seed and chemicals hence there is need for the market to share that knowledge with them. Such knowledge is very important for the young generation especially those born and bred in urban centres who have are keen to know the benefits of production techniques used to produce the food they consume.

The role of different actors in advancing or undermining African food

While there is some level of concern about the extent to which African food is not receiving the attention it deserves, most people think formal institutions and policies can make a difference.

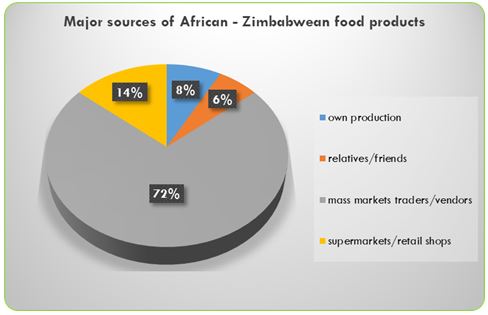

Figure 1: Major sources of African-Zimbabwean food products

- 72% of the respondents get their African-Zimbabwean food products from mass markets like Mbare, Lusaka in Highfield and PaDust in Haticliffe.

- 14% of the respondents buy African-Zimbabwean food products from supermarkets/retail shops, especially those from low density suburbs and those working in the Central Business District. Some of these households indicated they would have preferred buying from Mbare because of wider diversity and relatively cheaper commodities but they were pressed on time and distance to visit the market.

- 8% of own production is mainly the indigenous chicken by middle density suburb households like Waterfalls where they say have bigger spaces for fowl runs.

- Relatives and friends (6%) also play a part in distributing African-Zimbabwean food products especially as they travel to urban areas from their rural homes, they bring with them such food products and share with relatives and friends.

Role of food vendors and caterers

In recent years, Zimbabwe has witnessed an increase in open air leisure centres especially at shopping centres in high density suburbs and on the outskirts of cities. Common at these centres are food caterers who prepare different menus for diverse clients among them families, friends and sports fans. The survey team visited and interviewed food vendors operating at popular places that include Mereki in Warren Park D, Zindoga in Waterfalls and Mastones in Highfied. Findings from these places indicated:

- Increasing demand for traditional food over the years. Some customers especially men who eat traditional meals at these places claim their wives have no knowledge on how to cook while some complain about the long time it takes to cook traditional food, which also has a bearing on cost of power.

- Business is at peak during weekends, month end, public holidays and festive seasons. Major customers are sports fans, people from after social events/parties like weddings, graduations; social clubs especially soccer (maboozer); micro, small and medium entrepreneurs operating at these centres and their employees. Some formally employed consumers drive from their work places to these centres for lunch.

- The growing food vending sector is also following the increasing trend of the micro, Small and medium Enterprise (MSME) sector. Food vendors have become part of this sector’s ecosystem providing food to traders of food and non-food items in different locations of towns, cities and growth points.

- Residential food vendor businesses are for decades considered informal and illegal hence they lack: proper and formally designated work space and amenities, appropriate cooking facilities and as result some potential customers shun to eat their food or do business with them.

Role of restaurants

Restaurants are the main sellers of cooked food in cities and towns. In recent years, some restaurants have moved to specialize in traditional foods. Three such restaurants were visited and interviewed during the survey and provided the following feedback:

- Transitioning of some restaurants to traditional food has been informed by recent consumer trends where demand seems to be shifting towards traditional meals.

- Rather than preparing meals that wait for consumers, some restaurants prefer working more with orders although there tends to be walk-in consumers especially during lunch time and weekends.

- Meal prices range from USD2 to USD15 depending with meal composition and restaurant. Some customers feel the prices are too high and exclusive of the majority potential customers. As a result, some customers go to the restaurant when they are invited to an event or a better to do friends.

- What is also emerging is that when you are developing a market for indigenous food it is not easy to forecast consumption volumes and patterns in terms of how many plates of small grains meal per day since loyal customers will not be easy to determine. It will be more like cautiously shooting in the dark and trying to work with orders in terms of number of plates requested by formal institutions.

Fast food outlets

Over the past decades, fast food outlets have dominated the cooked food market share especially among the young generation and travelling cross border traders. One food outlet confirmed that in 2020 it opened 85 branches and it is still far behind plans to identify and get new sites approved for the food business. Findings on the food menus from two branches of different major fast-food companies reveal the following:

- Demand for fast food products is on the increase than ever before despite some complaining of harsh economic conditions and high unemployment.

- No traditional menus are prepared and served in these outlets.

- Top on the menu include chicken – broilers and fried chips.

Hotels and Lodges

Like many African countries, Zimbabwe is blessed with natural, cultural as well as human tourist attractions for foreigners as well as local citizens. The country has well-established hotels and lodges in towns, cities and tourist attraction locations. Chefs from two hotels and a lodge were interviewed during the survey and below are the summary findings:

- Menus try to respond to the needs of diverse customers. However, most people who stay at the hotel often consume whatever is available without asking too many questions except those with medical conditions that require them to consume specific meals including vegetarians. This shows the extent to which most consumers trust the Chef’s decision and judgement. It means Chefs have enormous power to influence what consumers can eat.

- Some foreign visitors prefer food types they know and consume in their home countries while very few want to experiment with new food.

- One big hotel has set aside a day for traditional menus where consumers are saved local food including wild animal meat. However, some traditional food items like mopane worms (madora/mancimbi) and roasted are becoming part of daily meals.

- Food procurement is through the buyers who adhere to a suppliers’ list and do not accept walk-in suppliers.

Role of hospitals

Even without scientific and academic knowledge the majority of African and specifically Zimbabwean consumers confirm that their local food is healthier and nutritious compared to western food. It was this survey’s intention to track what type of food they are served if these consumers are hospitalised. Chefs and Food Supervisors from two government and private hospitals were interviewed and summarised below are their responses:

- Menus are designed in close consultation with dieticians and medical doctors who prescribe what different patience should consume according to medical conditions. However, there are standard meals consumed by all patients including pregnant mothers. These comprise sadza, meat and vegetable.

- In some health institutions, traditional food menus are served twice or thrice per week and these include finger millet mainly for porridge and sadza. There is still less interest in pearl millet and sorghum. All types of dried & fresh indigenous vegetables, beef, sugar beans and indigenous chicken are served as relish.

- Demand for traditional meals and organically produced commodities is increasing especially in private hospitals where individual patients’ needs attention is more pronounced.

- In line with regulations by the Procurement Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (PRAZ), food is procured through registered organizations which also have to provide tax clearance. Chefs are also responsible for quality control to make sure the food procured meets health standards.

Role of higher tertiary institutions

The University of Zimbabwe is the first and biggest university in Zimbabwe with more than 10 000 students. On the other hand, Harare Institute of Technology (HIT) is renowned for technology designs and development including food processing. Being high institutes of learning with a large consumer base at one location, the survey got an interest to explore their food baskets and consumption patterns through interviewing the institutions Chefs/Food Managers. Below are the findings from the two institutions:

- Meals are mostly standard comprising sadza or rice with beef or chicken including additives like tomatoes, onion and leafy vegetables.

- At University of Zimbabwe African traditional food is only served at commercial canteens with the price ranging from USD4 to USD7 per plate depending on composition but this is far beyond reach of the majority of students. Such food include finger millet sadza, indigenous rice, all kinds of dried indigenous vegetables (mufushwa); boiled roundnuts & cowpeas (mutakura), sweet potatoes and mopane worms (madora). Menus are reviewed time to time and sometimes test runs for new meals are conducted.

- Sometimes the university is requested by big organizations like the UN to prepare food for events like World Mental Health Day. In some cases, the UZ prepares traditional food with an African theme.

- Procurement of food needs approval from the Procurement Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (PRAZ) which currently insists that tertiary institutions should buy food or any commodities from PRAZ registered companies or organizations.

- To supplement its food purchases, UZ grows and supply maize and fresh vegetables, onion, broccoli, cauliflower and others from its university farm which is often given production plans.

- Both UZ and HIT confirmed that preference for traditional meals has been increasing over the past few years as health consciousness increases among staff, ordinary people and students. This is buttressed by a recent study conducted by researchers at Chinhoyi University of Technology (CUT) which revealed growing appreciation for traditional food by the mature aged academics who see traditional food as a reference point for their indigenous cultural identity.

Boarding Schools

Boarding schools are more of the first home for learners as they spend much more time at school than at home during their learning years. The survey covered three boarding schools to assess their meals and consumption patterns and below are the findings:

- Some boarding schools are private and their food preferences for the pupils are dictated by family wealth.

- Menus are designed based on the five nutrients including carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins and others.

- Food is bought from formal supermarkets, schools own farms and sometimes mass markets like Mbare in Harare and Sakubva in Mutare.

- Based on their food knowledge, the Chefs try to balance starch with protein. However, they have discovered that most children do not like leafy vegetables and this goes back to how they were raised at home as well as the current meals being consumed at their homes. One of the main reasons why children do not like vegetables is because of the taste. For young people taste is a key determinant of consumption.

- The Chefs have had to improvise by combining different foods in order to enhance taste by for instance making a paste vegetable menu which children will not be able to separate into different components since it will be a wholesome meal.

- One school has introduced traditional Wednesday for promoting traditional food. While the children do not even like white sadza, they have embraced rice as their staple, not bread. This implies the nation should be promoting rice production in place of wheat production.

- May be more days should be set aside for traditional meals rather than one day per week.

- Food and Nutrition is studied as a subject but practicing what is learned is a challenge.

- Some menus are sports-oriented, being either carbohydrates or protein based, depending on the type of sport.

The value of riding on what is already happening

Across Africa, many organizations and stakeholders are already doing some work on African food and such work just need to be consolidated and documented. Promotion and consumption processes are already happening through relationships and silent channels. The campaign may consider learning from the way Africans promote their food systems which may be different from what happens in other parts of the world.

A lot of undocumented methods are being used to promote African food. Most communities are built around core food systems such that in some cases there may be no need to campaign because some food is part of people’s identity. In such cases, documenting practices to reveal what exists including how food is exchanged between relatives, households, markets, rural to rural, urban to rural and many other channels can be a good approach. Demonstrating intricate pathways through which African food moves will be quite revealing. Emphasis may be on using methodologies whose impact can be monitored, tracked and evaluated for the purposes of scaling up good practices.

charles@knowledgetransafrica.com / charles@emkambo.co.zw /

info@knowledgetransafrica.com

Website: www.emkambo.co.zw / www.knowledgetransafrica.com

Mobile: 0772 137 717/ 0774 430 309/ 0712 737 430